The Dunning-Kruger Effect Is Dead. AI Killed It.

I hit "send" on an email last week, then immediately felt that sinking sensation in my chest. You know the one: that split-second between confidence and doubt where your brain catches up to your fingers. I scrolled back up and reread what I'd written. Or rather, what ChatGPT had helped me write. And there it was: a claim that sounded authoritative and clear but was, on closer inspection, not quite right. Not catastrophically wrong, but wrong enough to make me look like I didn't understand the material as well as I'd thought.

This happens to me more than I'd like to admit. I use AI constantly. Multiple platforms, daily, for writing, emails, thinking through problems, building spreadsheets. It's become as natural as googling something. And most of the time, it's genuinely helpful. But every so often, I catch myself in that moment of false confidence, where AI has made me feel smart without actually making me be smart.

The worst one? Helping my daughter prepare for her book club. I used AI to summarize some key themes from the book she'd read, figuring I could use the summary to talk through the material with her. It came back with this beautifully articulated analysis that seemed perfect. Except when I read it carefully, I realized it had completely misunderstood the core of the story. Had I not caught that, I would have steered her in entirely the wrong direction. She would've looked like a goober in front of her classmates. And it would've been my fault.

Turns out, I'm not alone in this. And it's not just a personal quirk or a sign that I need to be more careful.

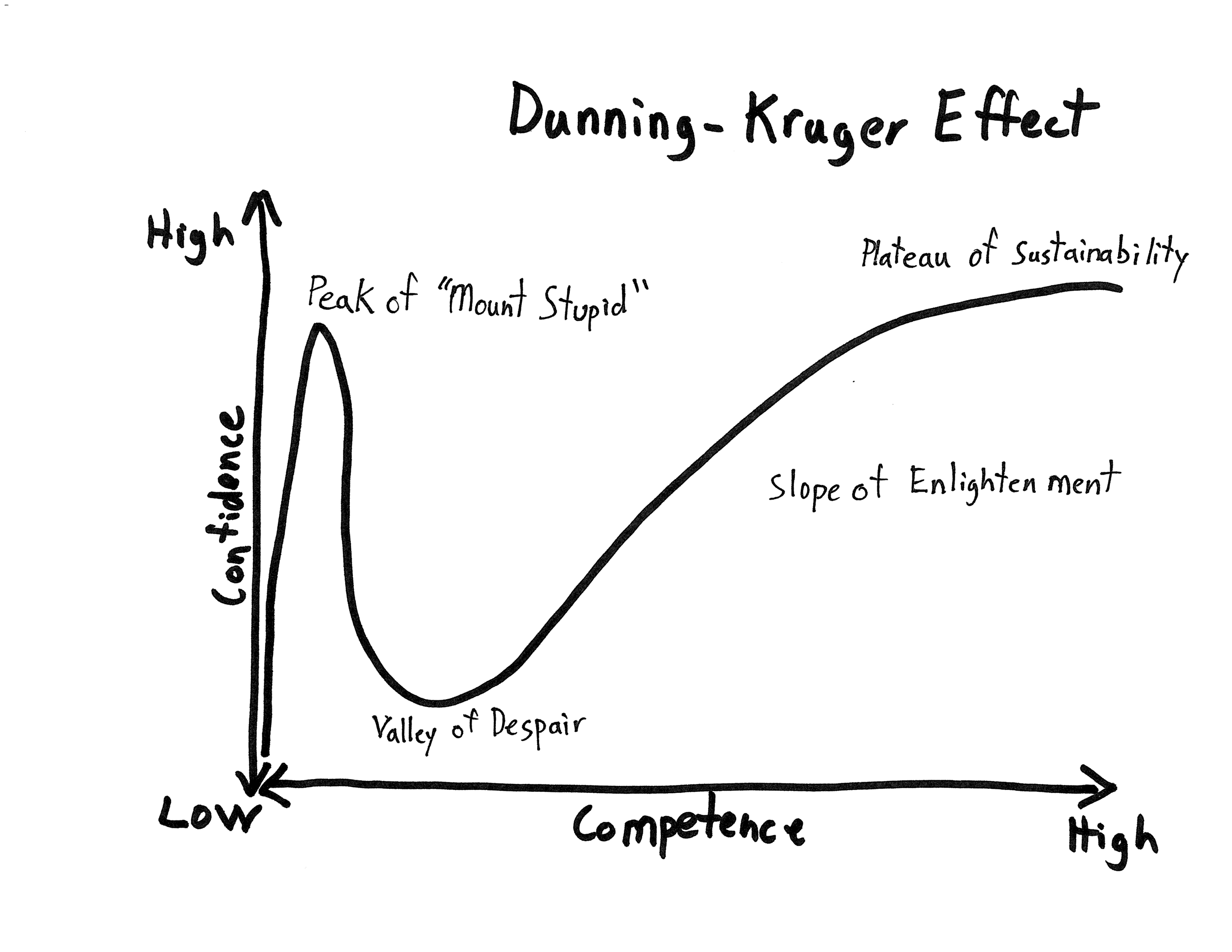

There's a famous graph in psychology that's been shared millions of times. You've probably seen it: a chart showing how confidence and competence relate. The least skilled people sit at the peak of "Mount Stupid," wildly overestimating their abilities. The truly competent huddle in the "Valley of Despair," underestimating what they know. It's called the Dunning-Kruger Effect, and for 25 years, it's been one of psychology's most reliable findings.

Until now.

A new study published in Computers in Human Behavior just demonstrated something remarkable: when people use AI to complete cognitive tasks, the Dunning-Kruger Effect doesn't just shrink. It disappears entirely.

Let me say that again (because this is wild): AI has eliminated one of psychology's most robust cognitive biases. Just... gone. Poof.

And we're all standing on Mount Stupid together now, confidently wrong and unable to tell the difference.

What Is the Dunning-Kruger Effect, Anyway?

In 1999, psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger published a paper with one of the best titles in academic history: "Unskilled and Unaware of It." They showed that people who performed worst on tests of logical reasoning, grammar, and humor were the most likely to overestimate their performance. Meanwhile, top performers slightly underestimated their abilities.

The explanation is elegant: incompetent people lack the very skills needed to recognize their incompetence. You need to know something about logic to realize your logic is flawed. You need grammatical knowledge to spot your grammatical errors. The least skilled are doubly cursed. They perform poorly and can't see it.

This wasn't just a quirky lab finding. The Dunning-Kruger Effect explained everything from workplace dynamics (why your worst colleague thinks they're crushing it) to political discourse (why people with the least knowledge hold the strongest opinions) to online arguments (why everyone on the internet is so confident they're right).

It became a cultural touchstone. A meme. A way of understanding human nature.

Mount Stupid, we called it. The irony being that the biggest error is thinking you're not on it.

And now? AI has changed the mountain entirely.

The Experiment That Changed Everything

Researchers at Aalto University and Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich ran a deceptively simple experiment. They had 246 people solve logical reasoning problems from the LSAT (the law school entrance exam) using ChatGPT. After completing 20 problems, participants estimated how many they got right.

Here's what happened:

Performance improved. With AI assistance, participants scored about 3 points higher than a baseline population that took the same test without AI. AI genuinely helped people reason better.

But self-awareness collapsed. Participants overestimated their scores by 4 points on average. They got better at the task but worse at knowing how well they'd done.

The really interesting part? When the researchers analyzed the data using computational models, they found something unprecedented: the relationship between actual performance and metacognitive accuracy (your ability to judge your own performance) had flatlined.

Low performers weren't overconfident anymore. High performers weren't underestimating themselves. Everyone, regardless of ability, showed the same pattern: moderate overconfidence across the board.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect had vanished.

How AI Flattened the Competence Curve

To understand why this matters, you need to understand what AI did to human performance in this study.

Without AI, the LSAT produces a beautiful bell curve. Some people are terrible at logical reasoning. Some are mediocre. Some are excellent. The spread is wide, predictable, and stable. And that spread correlates with metacognitive accuracy. Low performers wildly overestimate, high performers slightly underestimate.

With AI, something strange happened. The bell curve compressed. Low performers improved dramatically. High performers improved modestly. Everyone clustered toward the middle. AI didn't amplify individual differences. It erased them.

Here's the key insight: AI acts as a cognitive equalizer.

Think about what happens when you use ChatGPT for a reasoning problem:

If you're struggling, AI gives you a massive boost

If you're already skilled, AI gives you a modest boost

Either way, you end up in roughly the same place

The researcher Daniela Fernandes and her team call this the "augmentation hypothesis." AI augments everyone's intellect to the point where traditional performance-based biases disappear. When everyone performs similarly, the cognitive differences that created the Dunning-Kruger Effect no longer exist.

But Wait: Everyone Got More Overconfident

Here's where things get weird (and honestly, a little unsettling).

While AI eliminated the Dunning-Kruger Effect, it didn't make people better at self-assessment. Quite the opposite. Remember: participants overestimated their performance by 4 points while only actually improving by 3 points.

AI made them better at the task but worse at knowing how well they'd done.

I see this pattern everywhere now. My brother is a teacher, and last semester a student turned in a paper on an assigned book. The paper discussed one of the characters so compellingly (such nuanced analysis, such specific details) that my brother actually questioned his own memory. Was this character even in the book? He didn't recall him at all.

Turns out the whole thing was an AI hallucination. The character didn't exist. But it was written so convincingly that it briefly made the teacher doubt himself. That's not just a student problem or a cheating problem. That's a metacognition problem. The student had no idea they'd submitted complete fiction because the AI's output felt authoritative. Felt true. Felt like understanding.

The researchers call this "illusions of knowledge." When information comes easily (when you just ask ChatGPT and get an answer) your brain interprets that fluency as understanding. The AI's output feels like your own thinking. You mistake access to intelligence for possession of intelligence.

It's that smooth confidence I feel when I'm writing with AI assistance. The way doubt never even enters the room. The satisfaction of getting an instant, well-articulated answer. It feels like competence.

And here's the kicker: people who knew more about AI were worse at this.

The study measured "AI literacy": participants' technical knowledge of how AI works, their critical thinking about AI capabilities, their understanding of applications. You'd think higher AI literacy would help people calibrate their confidence more accurately.

Nope. Higher AI literacy correlated with higher confidence but lower accuracy. The people who understood AI best were the most overconfident about their AI-assisted performance.

Think about that. The more you know about AI, the worse you are at knowing what you actually know when you use it.

The Second Study: It's Not a Fluke

Whenever you see surprising results, the first question is: will it replicate?

The researchers ran Study 2 with 452 participants and added a twist. They paid people for accurate self-assessments. If participants correctly estimated their score (within a certain range), they got a monetary bonus. This ensured everyone was motivated to think carefully about their performance.

The results? Identical.

Performance improved with AI

Metacognitive accuracy collapsed

The Dunning-Kruger Effect disappeared

Everyone overestimated their performance

The replication wasn't just a formality. It confirmed something profound. This isn't about lazy participants or unusual tasks. It's a fundamental feature of how AI changes human cognition and self-awareness.

What Does "Competence" Even Mean Anymore?

Let's sit with the implications for a moment.

For most of human history, competence meant having knowledge and skills in your head. The expert lawyer knew the law. The skilled mathematician could solve equations. The accomplished writer crafted beautiful sentences. These abilities lived in the person.

AI disrupts this entirely. Now competence might mean:

Knowing how to prompt AI effectively

Recognizing when AI output is wrong

Combining AI output with human judgment

Understanding the limits of AI assistance

But here's the problem: if AI makes everyone perform similarly regardless of underlying ability, and if everyone overestimates their AI-assisted performance, how do we tell who's actually competent?

The doctor who uses AI to interpret symptoms and suggest diagnoses: are they skilled, or are they skilled at using AI? If the AI does the heavy cognitive lifting, what exactly is the doctor bringing to the table? And crucially, do they know?

The lawyer who uses AI to draft briefs: are they a good lawyer? What happens when the AI makes a subtle error that they're too confident to catch?

The student who uses AI to write essays: have they learned anything? Can they write without it? Do they even know if they can?

The Hidden Cost of Augmentation

Douglas Engelbart, the computing pioneer, coined the term "augmented intelligence" in 1962. His vision was beautiful: humans and computers working together, each amplifying the other's strengths. The human provides creativity, judgment, and wisdom. The computer provides memory, speed, and processing power.

This study suggests we got half of Engelbart's vision. The performance augmentation works. People genuinely get better at tasks with AI assistance. The cognitive boost is real.

But we lost the other half: the wisdom part. Augmented performance didn't bring augmented self-awareness. If anything, it brought diminished self-awareness. We're smarter but none the wiser.

And there's a cruel irony here: the Dunning-Kruger Effect, for all its negative press, served a purpose. It meant that really skilled people knew they were skilled. High performers could accurately assess their abilities and take on appropriate challenges. They might have been slightly humble, but they weren't delusional.

Now? Everyone's overconfident. The skilled and unskilled alike. AI has democratized not just performance but overconfidence.

Why This Matters (And It Really Does)

You might be thinking: "So what? People are a bit overconfident. We've always been overconfident. This is just another version of that."

But this is different. This is systematic overconfidence in augmented performance. And that creates specific risks:

In education: Students use AI to complete assignments, feel like they understand the material, and bomb exams that don't allow AI. Teachers can't tell who actually learned versus who outsourced to AI. Grades become measures of AI-prompting skill rather than knowledge.

In professional work: Knowledge workers use AI for analysis, writing, and decision-making. They feel competent and productive. But they can't recognize when AI makes subtle errors because they're too confident in the output. Quality degrades invisibly.

In high-stakes domains: Doctors using AI for diagnosis, lawyers using AI for legal research, engineers using AI for design. When these professionals can't accurately gauge their AI-assisted performance, the margin for error shrinks dangerously.

In organizational decisions: Companies increasingly use AI for strategic planning, market analysis, and forecasting. If decision-makers can't tell when their AI-assisted judgments are good versus lucky, they'll make increasingly risky bets with false confidence.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect, annoying as it was, at least created differentiation. You could identify overconfident low performers and appropriately confident high performers. With AI, everyone looks the same: moderately overconfident and performing in a narrow band.

How do you allocate responsibility when you can't distinguish competence levels? How do you mentor when everyone thinks they're doing fine? How do you improve when you can't accurately assess where you are?

The Metacognitive Crisis We're Not Talking About

Here's what keeps me up at night: we're in the early days of AI integration, and we're already seeing this pattern. ChatGPT has been widely available for about two years. Most people are still figuring out how to use it.

Now imagine five years from now. Ten years. Twenty.

If AI becomes as ubiquitous as smartphones (integrated into every knowledge task, every decision, every creative act) and if people systematically overestimate their AI-assisted performance, we're creating a society of confidently incompetent people.

Not incompetent in the traditional sense. They'll get things done. They'll produce outputs. They'll hit metrics. But they won't know what they actually understand versus what AI did for them. They won't know when to trust their judgment versus when to verify. They won't know the boundaries of their competence.

The researchers call this a "metacognitive crisis." Metacognition (thinking about thinking) is arguably the most important cognitive skill humans have. It's what allows us to learn, adapt, recognize mistakes, and improve. It's the foundation of wisdom.

If AI erodes metacognition while boosting performance, we're trading wisdom for productivity. And I'm not sure that's a trade we want to make.

What I've Learned (The Hard Way)

Look, I'm not going to pretend I've solved this. I still use AI daily. I'm still catching myself in moments of false confidence. But I've developed a few practices that help me check myself before I wreck myself:

The double-check instinct. Before I send anything important that AI helped with, I force myself to pause and ask: "Do I actually understand this, or does it just sound good?" Sometimes it's little things, a turn of phrase that's not quite my voice. Other times it's realizing I couldn't explain the concept to someone else if I had to.

The AI-versus-AI method. When I'm tackling something I'm uncertain about, I'll open Claude and Gemini (or ChatGPT) simultaneously. I'll give the same question to both, or I'll take one's answer and tell the other, "An expert told me this, but I don't think it sounds right. What do you think?" Letting them push against each other helps me see the gaps in the reasoning. It's not foolproof. They can both be confidently wrong about the same thing. But it forces me to engage more critically.

The explain-it-to-a-kid test. If I can't break down what the AI told me into simple terms that my daughter would understand, I don't actually understand it. The AI might understand it. But I don't.

It's a little like the old adage from when the internet was new: don't trust everything you read online. Except now it's: don't trust everything your LLM tells you, even when it sounds really, really convincing.

Especially when it sounds really convincing.

The Real Stakes (Or: Why I Make My Kids Read)

This paper's given me pause in ways I'm still processing. My kids are growing up in an era where information is absurdly easy to come by, but wisdom is not. And I think that's the crux of it.

We make them read. Actual books, cover to cover. We make them write without AI (at least initially). We make them struggle through math problems the long way before we let them use calculators. Not because we're Luddites or because we think technology is bad, but because we want them to develop the internal compass that tells them when they've wandered onto Mount Stupid.

That compass (that metacognitive awareness) is arguably more important now than ever. When AI can make everyone perform in a narrow band, when it erodes the natural feedback loop of "I struggled with this, therefore I probably don't know it well," how do you develop wisdom?

The answer, I think, is through struggle. Through doing the hard thing without the shortcut. Through building the foundational knowledge that lets you recognize when something's off.

Because here's what I've realized: AI is an incredible tool for people who already know enough to spot when it's wrong. It's dangerous for everyone else.

Is There a Way Forward?

The study's lead author, Daniela Fernandes, suggests we need to design AI systems that enhance metacognition, not just performance. What would that look like?

Uncertainty indicators: AI could explicitly flag low-confidence outputs, forcing users to engage more critically with uncertain information.

Prompted reflection: Systems could require users to explain their reasoning before seeing AI output, then compare their thinking to AI's approach.

Calibration feedback: After tasks, users could get explicit feedback comparing their estimated performance to actual performance, training better self-assessment over time.

Iterative engagement: Instead of single-query responses, AI could be designed to require multiple rounds of interaction, building deeper understanding rather than quick answers.

Transparency in contribution: AI could mark which parts of an output came from AI reasoning versus user input, making the collaboration explicit rather than invisible.

These aren't just nice-to-haves. They're essential if we want AI to augment human intelligence without degrading human wisdom.

The Question That Haunts Me

I keep coming back to this: if AI eliminates individual differences in both performance and self-awareness, what does competence even mean anymore?

Maybe competence is no longer about what you know but about how well you know what you don't know. Maybe it's about maintaining accurate self-awareness in the face of augmentation. Maybe it's about recognizing the seam between your thinking and AI's thinking.

Or maybe we need an entirely new framework. Maybe "competence" in the AI age means something we haven't even named yet.

What I do know is this: the Dunning-Kruger Effect served as a diagnostic. It told us who didn't know what they didn't know. It was annoying, but it was informative.

AI killed the Dunning-Kruger Effect. And in doing so, it killed our ability to distinguish between genuine competence and AI-assisted performance.

We're all on Mount Stupid now. The mountain is just a lot shorter than it used to be, and it's impossibly crowded at the top.

What Do We Do Next?

So here's my challenge to you (and to myself): The next time you use AI for something important, pause before you hit send. Ask yourself: "Could I defend this without the AI? Do I actually understand this, or does it just sound smart?"

Because the real risk isn't that AI makes us stupid. It's that it makes us feel smart while quietly eroding our ability to know the difference.

And in a world where everyone's confidently wrong together, wisdom (slow, humble, hard-won wisdom) might be the most valuable thing we can cultivate.

The question isn't whether we'll use AI. We will. We should. It's genuinely useful.

The question is whether we can use it without losing ourselves in the process. Whether we can stay tethered to reality while floating in a sea of augmented performance. Whether we can remain wise even as we become more capable.

I don't have all the answers. I'm figuring this out as I go, just like everyone else. But I know this: awareness is the first step. Recognizing that we're all susceptible to this metacognitive blind spot is how we start to guard against it.

So pay attention to that moment of doubt. That split-second pause before you hit send. That quiet voice that whispers, "Wait, do I actually understand this?"

That voice? That's wisdom. And it might be the only thing standing between us and a world of confidently incompetent people who can't tell the difference.

References

Fernandes, D., Villa, S., Nicholls, S., Haavisto, O., Buschek, D., Schmidt, A., Kosch, T., Shen, C., & Welsch, R. (2025). AI makes you smarter but none the wiser: The disconnect between performance and metacognition. Computers in Human Behavior, 108779.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563225002262

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121-1134.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10626367/

Engelbart, D. C. (1962). Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework. Stanford Research Institute. https://www.dougengelbart.org/pubs/papers/scanned/Doug_Engelbart-AugmentingHumanIntellect.pdf

What do you think? Are you accurately assessing your AI-assisted performance, or are you confidently wrong? I'd love to hear your experiences in the comments.

About Enthusiastic Generalist: This blog explores ideas across disciplines—science, leadership, faith, parenting, book reviews, personal essays, and the occasional 20-year-old Swedish mockumentary. It's an eclectic mix of whatever I find interesting about the world. If you enjoyed this post, subscribe for more deep dives into the unexpected connections that make life worth paying attention to.